By Anita Malhotra

Sandra Schulberg is a New York-based producer whose credits include Waiting for the Moon (Sundance Grand Jury Prize, 1987) and the Oscar-nominated Quills. Her most recent project, Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today, was shown at the 2010 Berlin Film Festival and is now making its away across North American theatres and film festivals. It’s a frame-by-frame restoration of a 1948 film made by her father, Stuart Schulberg, about the first Nuremberg Trial. The original film was shown in Germany as part of a postwar campaign to “denazify” and re-educate Germans, but was never shown in U.S. theatres.

Anita Malhotra spoke to Schulberg, who was at her New York office, by telephone on Thursday, Jan. 13, 2011.

Sandra Schulberg restored her father’s 1948 film in collaboration with documentary filmmaker Josh Waletzky

AM: I find it fascinating that you have in a way completed a circle by bringing your father’s film – which was never shown in North America theatres – to North American screens. Why did you decide to restore the film Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today?

Schulberg: The big impetus was when I saw the film for the first time in 2004 and began to look into what had happened in the U.S. with it. I learned that it had actually been suppressed and began to feel that there was a big hole that needed to be filled in terms of the reporting of the trial in the United States. This film had been produced by the U.S. government presumably for German and American audiences, and yet the second part of that equation had never been completed. So right away it occurred to me that there was a historical mandate.

Marine Corps Sgt. Schulberg, youngest member of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) Field Photo – War Crimes Unit (Schulberg Family Archive)

Also, we had recently emptied my mother’s apartment after her death and found an extraordinary cache of documents telling the story of the making of the film and all the political obstacles that my father and Pare Lorenz faced, Pare having been the person at the War Department who hired my father to make the film. As I began poring through these documents, I really became personally interested in the story, and I became more and more convinced that this was an untold story that should be told.

I don’t think I ever would have attempted it if I hadn’t been a filmmaker myself because, although I don’t think there’s any mystery to film restoration, I do think you have to be an experienced producer or director to undertake something like this. But that was a non-issue because I’ve been a professional producer for 30 years. So I had no excuse. I had the legacy that I had inherited and I realized that I was qualified to do it, so it was a matter of raising the money.

AM: How much did the film cost to make?

One of the films produced by Schulberg: “Waiting for the Moon,” a Grand Prize Winner at Sundance in 1987

Schulberg: In the end I was able to do it for about $120,000 over five years. This was without any money for myself, however, which was a tremendous challenge because I had to keep finding other ways to support myself while I was doing this. It was not that expensive and yet it was very difficult to raise the money. I think because the film is so unknown here in the United States, there was a big educational process involved and a lot of people didn’t realize how important it would be.

AM: For those who haven’t seen the film, can you briefly describe it?

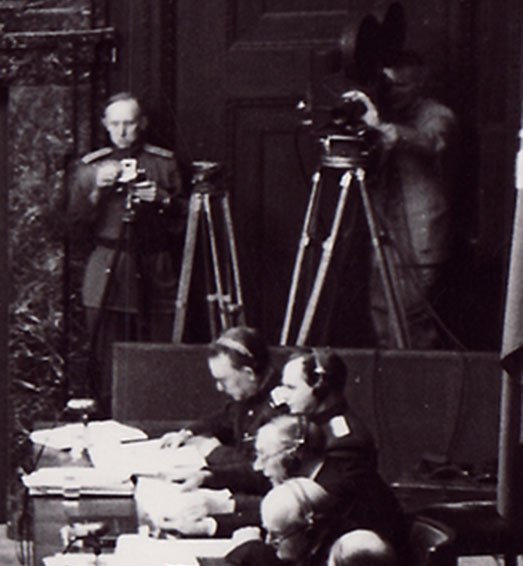

Schulberg: Nuremberg is composed of scenes that were shot in the courtroom over the course of a trial that lasted from Nov. 1945 until the verdict was rendered on Oct. 1, 1946. Those scenes are intercut with the evidentiary films that were presented in the courtroom, which my father had been involved in compiling and editing.

The two primary evidentiary films quoted in the film are The Nazi Plan, which was a four-hour-plus film that the Office of Strategic Services Film Team compiled for the courtroom consisting primarily of Nazi footage, and a one-hour film called Nazi Concentration Camps, which consisted primarily of American and British films that were shot when the camps were liberated.

Defendents in the first and best-known Nuremberg Trial: First row, L to R: Hermann Goering (death sentence), Rudolf Hess (life in prison), Joachim von Ribbentrop (death sentence) and Wilhelm Keitel (death sentence) (NARA photo)

There’s also a very historically important piece of film – just a few seconds of it that is included in the film – called the Mogilev footage, which my father found in the Berlin apartment of an SS officer named Nebe. It is considered to be the Nazi documentation of the still experimental use of gas to kill human beings, and it’s very dramatic footage.

AM: Tell me about the search for the footage that went into the evidentiary films, and then into Nuremberg.

Budd Schulberg supervised compilation of the evidentiary films shown at the first Nuremberg Trial. He later wrote the script for the 1954 film “On the Waterfront.” (Schulberg Family Archive)

Schulberg: What I know about all that comes from my uncle Budd Schulberg, who was a Navy Lieutenant in the special film team that was assigned to work with Justice Jackson’s office preparing evidence for the trial. John Ford, who was the head of that film unit based in Washington, sent Ray Kellogg, my uncle Budd, and my father Stuart to Germany in the months preceding the trial to locate Nazi films and photographs that Jackson hoped to use in the courtroom as evidence.

Stuart (L) and Budd (R) – sons of former Paramount Pictures executive B.P. Schulberg – worked in the same OSS Film Unit (Schulberg Family Archive)

My father was the first of the unit to be sent over, arriving in Europe in June of ’45. Budd didn’t arrive till about August, and then the film editors got there mid-September. By that time the trial had been postponed several times, so that they had just enough time to find what they needed. Budd describes the fact that they found several caches of film still smouldering or burning when they came upon them, and they came to suspect that this material was being sabotaged by the people who were holding the material and who didn’t want it to fall into Allied hands. But eventually they did find enough material to put together this four-and-a-half-hour-film.

AM: The German version was widely shown in Germany in the late ‘40s. What kind of a reception did it get?

German moviegoers in 1948 leaving the Kamera theatre in Stuttgart after seeing “Nuremberg” (Schulberg Family Archive)

Schulberg: When you look at the first audience polls it’s really fascinating because the responses were just so extraordinarily varied, ranging from, “This is just propaganda and none of this ever happened” to people being really personally devastated and making comments like, “Now we finally know what happened” and “Every German should see this film.” I think it’s been well-documented in the postwar period that many Germans were unwilling or unable to accept, even in the face of quite concrete evidence, what had happened.

Original poster for “Nuremberg’s” 1948 German release. The Berlin run was delayed until May 1949 because of the Soviet Blockade (Schulberg Family Archive)

And my father documented that also in his personal letters, saying that when he first arrived there and first located the films that were used at the trial, many ordinary Germans that he came in contact with didn’t believe that it was real.

AM: The film was never shown in the U.S. Why?

Schulberg: It was suppressed because our U.S. policy had shifted. One of the very uncomfortable things about the film is that the Americans are shown in the course of the prosecution to be allied with the Soviets, and by 1949, when the film had been completed and they were contemplating releasing it in the U.S., that was just politically incorrect. U.S. policies had become anti-Soviet and extraordinarily anti-Communist, so that conflicted with our policy priorities.

One of the posters created by the Economic Cooperation Administration to sell the Marshall Plan in Europe

We had also launched the Marshall Plan. A key element of the plan was the reconstruction of Germany’s industrial infrastructure as an engine of European recovery, and they thought that if this film was widely shown it might turn Americans against Germany all over again. I think that’s quite possible. Although they were careful in the course of the film and in the course of the trial not to indict the German people per se but to really put the focus on individual leaders, nonetheless by implication, I think people watching the film would be reminded again of how much they hated Germany.

There’s another piece of this that is very interesting. There were members of our own military were opposed to the whole concept of bringing military officers to trial in an independent tribunal as opposed to military court-martial. Even though at issue was the fact that German military officers were being put on trial, there was this sense of solidarity amongst some military leaders who were opposed to this kind of tribunal for applying this kind of international criminal law to military officers.

AM: What might have changed had it shown in the U.S.?

Only 25 hours of footage were shot by U.S. Signal Corps cameramen during the 10-month trial, posing a challenge in the “Nuremberg” editing room

Schulberg: Well, that’s a matter of pure speculation. But I’ve become very curious about what people did see, and I think it was very, very fragmentary. You know, maybe dribs and drabs of certain atrocity footage, but really very little about the prosecution of the trial itself. One has to remember that this was an era before television when people got their news either through newspapers or on radio, or by seeing newsreels in the theatres. And to really see the defendants and the prosecuters at work, you would have had to see that in newsreels.

AM: What kinds of emotions did you go through during the restoration of the film?

Schulberg: During the period I was working on it I had this sort of single-minded determination to get it done, but not very much confidence because I was having so much trouble raising the money. It was a real struggle personally for me to do it and I was also very concerned about the impact it would have on German-American relations and on Jewish-German relations. I didn’t want the film to be viewed as a way of beating up on the Germans all over again.

Von Ribbentrop signing the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact on Aug. 23, 1939 (with Stalin behind him). The treaty contained a secret protocol outlining how Central Europe would be divided between the two powers (German Federal Archives)

Then there’s the separate question of the emotions you feel watching the atrocity footage or watching Hitler over and over again. Because I was researching and reading a great deal of material during these five years, I came to have a much deeper understanding of how effective Hitler was as a strategist, how effectively he pulled the wool over the eyes of his fellow European leaders and the Americans. And I think this is very graphically and effectively presented in the film. So many times watching the footage of him I was just marveling that this person, who seemed in the footage to be a raving megalomaniac, was actually very clever – much cleverer than he seemed.

As for the images of the people who are persecuted and killed in the film, I never became inured to that. It’s very disturbing to me every time I watch it. These people become real people to me. I know all the faces in the film, and there are times, of course, when you burst into tears when you just feel the pain.

A group of Hungarian Jews arriving at Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in May 1944, where they would have been subject to a selection process. An estimated 475,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz between April and July of 1944 (German Federal Archives)

AM: One of the best-known people working on the production is Liev Schreiber. How did he come on board?

Actor Liev Schreiber (the “Scream” trilogy, “RKO 281” and “The Manchurian Candidate”) narrates “Nuremberg” (Arcieri & Associates)

Schulberg: For many years I wanted Walter Cronkite to do the narration, and I had been in discussion with his office because Cronkite was one of the journalists present for some of the trial, and you can see him in the film. But unfortunately he died shortly before I was to re-record the narration. [Co-creator of the film] Josh Waletzky’s companion Jenny Levinson suggested Liev, which I thought was an excellent idea, and I contacted a mutual friends of ours, who sort of gave me entree to Liev. And he agreed to do it. He does an extraordinary job.

AM: To me the musical score sounded very authentic, but I understand it’s been reconstructed. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Schulberg: The musical score is the same one that was composed by Hans Borgmann, but we had to completely reconstruct portions of it – not every cue – but a lot of it.

Because the original sound elements of this film were lost or destroyed, we had to recreate the whole soundtrack from scratch and that included those portions of the music that were married to the old narration. So Josh Waletzky knew an extraordinary composer named John Califra, who was able to listen to the original music, notate it, and then recreate the same music using a synthesizer. Then we dirtied it up in the sound mix so that the audio quality would match the audio quality of those pieces of the original music that we could save and make it all seamless. It was a miraculous process.

AM: How is the film being distributed?

Schulberg: We have a lot of requests based on the New York premiere and the extraordinary reviews and articles. And so there are many theatres that want to play it. The problem is that I have no funding for distribution and there are certain expenses that you have to be able to meet, like the cost of film prints, film trailers, posters, postcards, and booking agents. I’m already in debt to the laboratory for about $25,000. We’ll see whether the film is able to break even and pay back the cost of the prints. How the film does as we roll out across the country, I just don’t know. It’s hard to predict when you don’t have money for advertising and you’re competing in a very crowded media environment.

AM: What has the reception of the film been like?

Schulberg: My main reaction showing this film is a feeling of gratification because it’s now become clear that the film has a historical importance, that it is filling a big hole in the historical record, that people are recognizing that it is old but at the same time new, and very revealing. So I’m hearing a great deal of appreciation from audiences and from historians and from international criminal justice experts, some of whom say Nuremberg is a fount of all of what we do in the modern era in terms of trying to hold people accountable for all kinds of crimes against humanity. So this is very gratifying.

Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today is now playing at various theatres. For more information about the film, visit the website www.nurembergfilm.org.

Excellent interview, Anita! Do you know if this is coming to Toronto?

LikeLike

Hi Mark,

I am not aware of any upcoming screenings in Toronto, although the film did premiere last April at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival. Here’s a link to an article about the premiere: http://www.thestar.com/entertainment/movies/article/795886–long-overdue-premiere-for-nuremberg.

Sandra Schulberg did mention a few weeks ago that she had a tentative screening set up in Montreal at the end of March, but I’m not sure if this has been confirmed. Her website http://www.nurembergfilm.org/ lists upcoming screenings in the tab “See the Film,” but Toronto or Montreal are not listed.

Thanks,

Anita

LikeLike

I forgot to say, it’s also refreshingly well illustrated with remarkably precise and pertinent photos and videos.

LikeLike

Found this to be highly interesting. Not only is your interview with Sandra Schulber extremely well carried out but her re-creation of the film must have been both difficult and harrowing. I would like to offer her my best wishes for success.

LikeLike